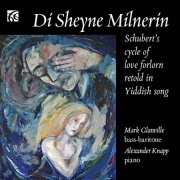

Di Sheyne Milnerin

Our recording comprises a specially devised cycle of twenty songs from the Yiddish repertoire — only the second time a collection of Yiddish songs has been forged into a narrative cycle with a coherent dramatic trajectory. A stark contrast to our Holocaust-focused programme, A Yiddish Winterreise, it explores and reveals different aspects of the Yiddish tradition. As in Schubert’s original, Die schöne Müllerin (‘the beautiful miller girl’), from which it takes its name, it tells a story of unrequited love. Here, the Jewish hero, though also a miller, is an older man with more than a little of Don Quixote about him, prone to tip at his own windmills and women who fit his idealised notion of love. Does he ever actually make contact with Reyzele, the object of his affection, or does he commune with her only in his dreams? Whatever the case, his sense of pain at being rejected in favour of the thief (replacing the hunter of Schubert’s cycle), who has stolen her from him, is the same. Nevertheless, interspersed among the expressions of tragic emotion may be found moments of joy, tenderness and humour. We both come from a Western classical music background; the songs are therefore not performed in the customary folk/popular style, but in the manner one might expect of a Lieder recital. The aim here — as in A Yiddish Winterreise — is to introduce this wonderful music to as wide an audience as possible, especially one brought up listening to the classical European repertoire, who may be unfamiliar with the Yiddish tradition.

Our recording comprises a specially devised cycle of twenty songs from the Yiddish repertoire — only the second time a collection of Yiddish songs has been forged into a narrative cycle with a coherent dramatic trajectory. A stark contrast to our Holocaust-focused programme, A Yiddish Winterreise, it explores and reveals different aspects of the Yiddish tradition. As in Schubert’s original, Die schöne Müllerin (‘the beautiful miller girl’), from which it takes its name, it tells a story of unrequited love. Here, the Jewish hero, though also a miller, is an older man with more than a little of Don Quixote about him, prone to tip at his own windmills and women who fit his idealised notion of love. Does he ever actually make contact with Reyzele, the object of his affection, or does he commune with her only in his dreams? Whatever the case, his sense of pain at being rejected in favour of the thief (replacing the hunter of Schubert’s cycle), who has stolen her from him, is the same. Nevertheless, interspersed among the expressions of tragic emotion may be found moments of joy, tenderness and humour. We both come from a Western classical music background; the songs are therefore not performed in the customary folk/popular style, but in the manner one might expect of a Lieder recital. The aim here — as in A Yiddish Winterreise — is to introduce this wonderful music to as wide an audience as possible, especially one brought up listening to the classical European repertoire, who may be unfamiliar with the Yiddish tradition.

‘Am Feierabend’, from Die schöne Müllerin, is placed almost half-way through the cycle. The German text by Wilhelm Müller has been translated into Yiddish by Heather Valencia, and the song retitled ‘Nokh der Arbet’. Arrangements and compositions by celebrated Jewish composers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have been included in this programme in order to extend and enhance the great Yiddish art song tradition, so keeping it alive and vibrant. Most are familiar masters of this genre. Others, however, are more obscure. Take, for example, Janot S. Roskin, who was born near Vitebsk, Belarus, in 1884. In his early life he travelled extensively, collecting traditional Jewish songs and arranging them in a style similar to that of the composers of the pioneering ‘Society for Jewish Folk Music’ founded in St Petersburg in 1908 (although he never became a formal member of this group). Subsequently, he relocated to Berlin where he founded a music conservatory. In 1916 he established a music publishing house which, five years later, was renamed Hatikvah, and whose purpose was to disseminate Jewish music. In the 1930s he emigrated to the USA, where he worked as song composer, synagogue choirmaster and conductor of a chamber choir and orchestra in Indianapolis. Hatikvah was relaunched in 1941 and eventually taken over by Transcontinental Music Publications, New York. Roskin, whose musical idiom was characterized by dramatic effects, including abrupt contrasts of mood and tempo, died in Indianapolis in 1946. Three of his arrangements have been included in this recording.

As with A Yiddish Winterreise, in part the programme functions as an acknowledgement of the rich symbiosis that once existed between the German and Jewish cultures, one of the many intangible victims of the Holocaust, during which members of both our families were murdered. Above all, though, it is a celebration of Yiddishkayt.

For Di Sheyne Milnerin Alexander Knapp has created eight completely new arrangements and one original composition. In doing so — and in common with the artist Liorah Tchiprout, whose original painting A sheyn lid hob ikh gezungen was commissioned as the cover for the CD — he celebrates and extends a still vibrant, Eastern European Jewish cultural tradition which, having been extirpated in its homeland, continues to thrive in and inspire the descendants of those who once nurtured and cherished it.

Alexander’s settings reflect a number of musical influences:

there are resonances of Bloch, Messiaen, Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Schubert, Sibelius—and Joe Loss — to name but a few. Though broadly tonal/modal in character, the harmonic language reveals frequently shifting tonal centres and chromatic dissonances, as well as hints of dodecaphony on the one hand and Eastern-Ashkenazi nusach (modal system) on the other. Motifs generated by the vocal melody are often utilized in the accompaniment, sometimes in disguised forms (e.g. canons, inversions, retrogressions and retrograde inversions), and they are integral to the piano interludes — sometimes strident, sometimes meditative — that link one verse to another.

Though the songs are mainly strophic, the arrangements are through-composed. And, since wordpainting is a central feature of the style, melodies from the wider Jewish and Classical repertoires are occasionally introduced as counterpoints to the main themes, in order further to emphasize particular associations of ideas. Whereas the melodic contour of each song is retained intact, occasional modifications of phrase length, rhythm and pulse have been introduced for expressive purposes. But it must be stressed that these are in no way intended as ‘improvements’; in every case the original version is beautiful, authoritative and perfect. Here the intention is only to give special expression to those facets that appeal most immediately to the arranger. The emotional range of the songs is vast and all-encompassing, from the liveliest wit to the deepest pathos. All these moods are evoked by exploring the full range of the keyboard.

A few words about each of Alexander’s settings will suffice: ‘Dodi li’ has a lilting Middle Eastern aroma, and builds to an emotional climax in the middle of the song before falling back to the wistful mood with which it began. ‘Tumba’ is full of jazzy syncopations and chord progressions, and tapers off mischievously in keeping with the narrative. ‘Bistu mit mir broygez’ tells the story of love triumphing over anger. Typical motifs of the Lern Steiger (in the Magen Avot mode) are introduced into the accompaniment to suggest the Rabbi’s heartfelt prayer for reconciliation between the warring factions. Peace gradually descends and the song ends with a distant echo of the Rabbi’s tune. ‘Himen’ (Anthem), a setting of the eponymous Abraham Sutzkever poem, is an original composition; it serves as a tribute to the great Yiddish poet, who died in 2010. The music is in the style of a dignified wedding march. There are two main themes which appear in alternation. Near the middle of the song there are quotations from one of the traditional Ashkenazi tunes for Kol sasson v’kol kallah (the short choral section in the last of the Sheva Brachot—‘Seven Blessings’—of the Wedding Service), as well as the melody of the traditional lullaby ‘Yankele’.

Beginning with a deliberately extravagant piano introduction, ‘Dem gonefs yikhes’, a scurrilous romp in the Freigish mode, progresses through a series of increasingly truculent moods, culminating in a cascade of percussive rhetoric. ‘Tzvey taybelekh’, which follows immediately, is as contrasted as could be. The shimmering accompaniments allow the voice free rein to explore the harrowing pathos of the text, sung in the style of a traditional cantorial recitative. The setting of the third of the four verses is particularly anguished, yet the piano coda moves from dissonance to consonance, representing the two doves in perfect harmony at the end. ‘Vu iz dos gesele’ is a nostalgic song describing the descent from high expectation to despair, as reflected in the contrast between the florid accompaniments of the first two verses and the starkness of the third. The text of ‘Es drimlen di lodns’ is altogether bizarre, and the setting is correspondingly quirky, with its twists and turns, abrupt contrasts of timbre, and its frequently impressionistic and atonal harmonization of a thoroughly diatonic melody in the minor key. The last song of the cycle, ‘Di zun vet aruntergeyn’, pays homage to Schubert’s much loved ‘Ständchen’, and also—in the last verse—to the rippling figurations that characterize Janot Roskin’s arrangement of Mark Warschawsky’s ‘Dem milners trern’, with which the entire cycle began.

Di Sheyne Milnerin was first performed at the Jewish Museum, London, in November 2010, and received its American première at Symphony Space, New York, in February 2011.

© Mark Glanville & Alexander Knapp 2011